Todd Tarbox, grandson of Roger Hill, headmaster of the famous Todd School for Boys, Woodstock, Illinois, along the progressive approach of A.S. Neill’s Summerhill, and the son of Hascy Tarbox, younger classmate and perhaps rival to Orson Welles contacted me after seeing some reference to Welles by me. Over the years, hear and there, I have written about Welles and Citizen Kane. I devote one chapter in my recent book to Welles. And what is that attraction?

Todd Tarbox, grandson of Roger Hill, headmaster of the famous Todd School for Boys, Woodstock, Illinois, along the progressive approach of A.S. Neill’s Summerhill, and the son of Hascy Tarbox, younger classmate and perhaps rival to Orson Welles contacted me after seeing some reference to Welles by me. Over the years, hear and there, I have written about Welles and Citizen Kane. I devote one chapter in my recent book to Welles. And what is that attraction?

I am appalled by what this culture, other cultures, do to the artist. The average Joe may or may not be emotionally impoverished; however, the real artist is never poor. That is a line from Babette’s Feast. Throughout his career critics faulted Welles for his incomplete and unfinished films. I ask you: what human being is not a mess of unfinished business when he comes to die? Why this envy of Welles and the need to tear him down. The appealing aspect for me is how Welles fought this off all his life and elements of that resistance are in this book.

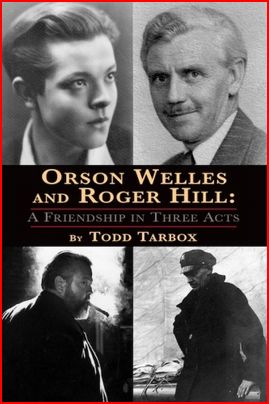

Of course, Tarbox’s book is the kind of book we cinephiles read while chewing Jujyfruits; it is absorbing, illuminative, informative, often provocative and with all the minutiae that fans want to know about Welles’s life, this man with an IQ of 185. So I read it straight through the night; it was not an analysis of the relationship between Roger Hill, the mentor, and Welles, the mentored; it was beyond that. What we have here is a delicious artifact, tapes that Hill-Welles kept of their conversations over the years, knowing full well that each was an important part of the other’s history. They both had a mastery of Shakespeare and often one would begin a quotation from the Bard only to have the other complete it; both their memories are astonishing.

What is salient here is the connection between a 70 year old and a 90 year old, the sustaining intellectual and emotional content of their conversations, the vigor in which they are expressed. Although the remembrance of things past is richly embroidered — that actor, that school play, that show, it really reveals how Roger Hill viewed Welles as a foster son if you will and loved him for his very being! That is Hill’s contribution, as I see it. Welles did not have to meet any expectations as the boy wonder; the world would sordidly go after him for decades on that hobbyhorse. The book is about love, the reciprocal exchange of love. Todd Tarbox should follow up with a book about his own father who is also an intriguing presence; he chose to stay close to the hearth of Hill, even marrying his daughter, while Welles flew the coop, but not entirely. He chose to maintain a friendship over decades — how many of us can say that? or have the staying power for such a relationship? or the opportunity?

In psychoanalytic lore, if I remember the rubrics, it’s been some time since I practiced; there is the concept of the “hold.” Think of the therapist presenting the client with a giant trampoline, encouraging him to bounce and cavort all he wants, knowing full well that he is safe and secure, that no judgment will be made; to know what it is to be enjoyed as a human being unconditionally. Roger Hill gave Welles that support. Often he ends a phone conversation with words of love, of encouragement; often his words are nurturing and admiring without being a sycophant. He enjoyed Welles’s genius without extolling it; he admired the boy who grew into a great artist and man. Although his works won Hill’s admiration, the thrust of the book is that Welles as a person was his best accomplishment. That is why Welles went back and back to Hill, for he was loved.

I must say here that there is dissenting material, lots of it, about Welles as a man; genius can be insufferable and often we need to cover our eyes before it, think of Salieri and Mozart. Nevertheless, Welles is revealed here as open, greatly liberal, free of racism, and tender. I recall this man who chose not to go to college telling his daughter (Chris Welles Feder) that the world was her curriculum and go forth and taste of it; she recalls how one day he took her through Rome explaining what this building or that statue meant historically, enriching her from his own vast treasury of experiences (he is rumored to have read one or two books a day).

Roger Hill was an inner-directed stoic, whose appeal as I sense it, was his capacity to deal with life moment to moment, as we discover Welles and he periodically threading their talks with the denial of death, the breakdown of the body from ageing, of living, of dying, of what is and is not important in the world. Welles is a fountainhead of information which he shares with Hill who takes it in and often asks for more, or clarification; Hill is not threatened by Welles knowledge which may have been one of the emotional ties that Welles appreciated. Welles detested cant of any kind.

I can sum it up, for it is not hard to do: Hill, as depicted in the book, was a free and liberated human being and was not threatened by that same blessing in any other human being. Hill, in fact, encouraged that in his students, to be free, not to be disciples, for that is deadly and Welles drank deeply from that. At the same I must caution that all is not simple between human beings and not all of the complexities of both men are revealed here, or can be.

Leave a Reply