…That once there was a wisp of glory called Camelot...Don’t let it be forgot That once there was a spot For one brief shining moment that was known As Camelot

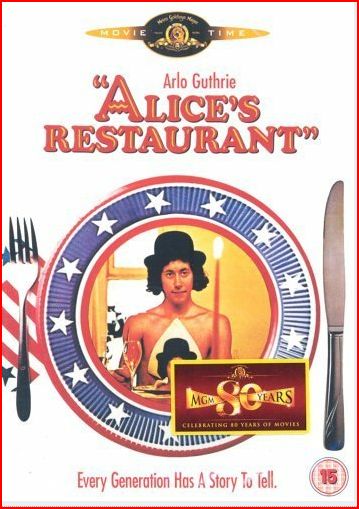

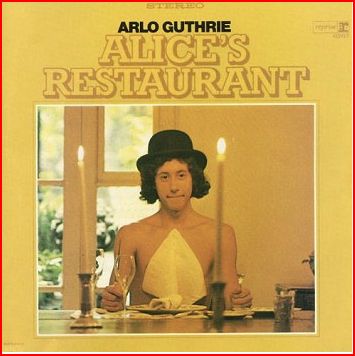

Director Arthur Penn had the prescience to make a film about the Sixties, Alice’s Restaurant, and in this instance, the waning of that era, 1968 and 1969. (The title came from Arlo Guthrie’s album of the time. Unique in that one whole side  was devoted to one song, 18 minutes or so.) And he had the intelligence to make it while the era was going on. In many ways the film is an unintentional documentary of the times. Two other films, A Walk on the Moon and Hair have been able to capture here and there the perfume of those times, but they came after the Sixties had ended. Alice’s Restaurant, for me, captured the ineffable. I remember little of seeing it in 1969 but as I reflect through what is a dim recollection I was touched by the sadness of the film, or perhaps my own sense of lamentation for what was now ending. I had the serendipitous good fortune to have spent two summers, ’68 and ’69, in Woodstock. I had lived it.

was devoted to one song, 18 minutes or so.) And he had the intelligence to make it while the era was going on. In many ways the film is an unintentional documentary of the times. Two other films, A Walk on the Moon and Hair have been able to capture here and there the perfume of those times, but they came after the Sixties had ended. Alice’s Restaurant, for me, captured the ineffable. I remember little of seeing it in 1969 but as I reflect through what is a dim recollection I was touched by the sadness of the film, or perhaps my own sense of lamentation for what was now ending. I had the serendipitous good fortune to have spent two summers, ’68 and ’69, in Woodstock. I had lived it.

I associate easily now to Camelot that I saw in 1968. Deeply moved by Richard Harris’s plangent rendition of what was the last song in that lush musical, King Arthur instructs a page to go tell the world that there was a fleeting moment that was Camelot, if I recall the words. It is a sentiment that roils one’s sensibilities. That “fleeting moment” also applies to my experiences in upstate New York. I was 28, I was 29 and I was an emotional sponge, absorbing everything about me — the head shops, the flamboyant dress, the beads, the bell bottom jeans, the sideburns and long hair, the middle-aged women getting off city buses in the town square of Woodstock acting as if they were missing something — indeed, they were; the real artists who inhabited lovely homes outside Woodstock, a few that I got to visit and chat with. The Elephant restaurant in which I annoyingly asked for my burger after what I felt was an inordinate time to wait and faced with the immortal answer, “It’s cookin’.” Ah, yes, time.

I associate easily now to Camelot that I saw in 1968. Deeply moved by Richard Harris’s plangent rendition of what was the last song in that lush musical, King Arthur instructs a page to go tell the world that there was a fleeting moment that was Camelot, if I recall the words. It is a sentiment that roils one’s sensibilities. That “fleeting moment” also applies to my experiences in upstate New York. I was 28, I was 29 and I was an emotional sponge, absorbing everything about me — the head shops, the flamboyant dress, the beads, the bell bottom jeans, the sideburns and long hair, the middle-aged women getting off city buses in the town square of Woodstock acting as if they were missing something — indeed, they were; the real artists who inhabited lovely homes outside Woodstock, a few that I got to visit and chat with. The Elephant restaurant in which I annoyingly asked for my burger after what I felt was an inordinate time to wait and faced with the immortal answer, “It’s cookin’.” Ah, yes, time.

A little outside Woodstock was a massive church that was built during the Depression, probably a WPA project,with stout timber, overhead rafters, stolid history, heavy doors with ornate wrought iron creatures applied to the wood, arts and crafts style — frogs, bugs, spiders, things like that; it later, much later, became a Buddhist center. And there was an old Catholic priest who lived on a nearby small mountain in a log cabin and church who people had visited for years just to say they had done so, to acquire his “wisdoms”; and he had old tapestries in the small church that he said were given to him by Marshall Field. I recall a trinket from his conversation with me, that at one time there were bears on that mountain. Was this a scene out of The Razor’s Edge? Many years later I came again to see him but learned he had died, his affairs left unsettled, and I saw his old rooms in the back of the church all gutted by the wind, snow on his desks, scattered testaments and assorted religious paraphernalia on tables as if a scene out of Lost Horizon.

I stayed for two summers at the home of a teacher friend. I remember two young people voicing their regretful frustration that they couldn’t get to the Woodstock festival which was really in Bethel because the New York Thruway had been shut down because of the traffic — an unheard of event for the time. I remember going swimming in a local pond filled with groups of young people, younger than me — I felt like a voyeur — completely nude, having fun and I began to lose, if only slightly, some of my uptightness as a human being. And the tits weren’t bad at all, nor the voluptuous asses. Ah, Monet on the rocks. Shedding the integument of the cosseted Fifties, I was becoming a human being. Are you, reader, or have you ever been aware of becoming a human being? It grabs you from behind, a delectable pickpocket, except something is given you rather than purloined.

I stayed for two summers at the home of a teacher friend. I remember two young people voicing their regretful frustration that they couldn’t get to the Woodstock festival which was really in Bethel because the New York Thruway had been shut down because of the traffic — an unheard of event for the time. I remember going swimming in a local pond filled with groups of young people, younger than me — I felt like a voyeur — completely nude, having fun and I began to lose, if only slightly, some of my uptightness as a human being. And the tits weren’t bad at all, nor the voluptuous asses. Ah, Monet on the rocks. Shedding the integument of the cosseted Fifties, I was becoming a human being. Are you, reader, or have you ever been aware of becoming a human being? It grabs you from behind, a delectable pickpocket, except something is given you rather than purloined.

It is beyond my writerly skills to capture the monarch butterfly that was Woodstock. I am left with shards, like stained glass pieces in my palm. What I remember was a special atmosphere, of a rock band playing in some back room in a house that fronted the street, the coffeehouses that introduced me to cappuccino, the tiny bridge that crossed the stream in the middle of town that coursed into the woods, the complex, varied and interesting stores that catered to tourists with T-shirts, and other accouterments of the era — head shops were antique stores in those days, everything arrayed in whatever assortment you chose. Given my rearing, I got high on art – for some reason, light boxes were the trend, relationships, sights and scenes and have no regrets for it. I was totally aware of what was happening to me to the extent that I could be. I was limited child trying to become a man. I was now open to experience.

Something had happened. Sounds like Joseph Heller‘s novel. Something had happened to me, was happening to me. For several years deep into the Seventies I would travel upstate, often in winter, leave my wife– she understood my need, and daughter at home and take a pilgrimage to Woodstock. I would buy a hot steaming cup of coffee, a sandwich of cheese and ham slathered with mustard on beautiful home baked slabs of dark raisin bread, the bread loaves slumbering in the store window. I visited a local lake which was frozen over, placed the coffee on the dashboard, the steam misting up the windshield, the sandwich to my right on the passenger seat. Nothing was in my mind except all the memories of that lake. Years later I’d take students up to the lake in the spring and winter to allow them to capture twice-fold only one essence that I had experienced.

(Look everyone, share with me everyone, it is here that I changed, I grew, began to feel who I was and to put away thinking for a while — what was the slogan then, die to your mind and come to your senses.)

On one visit I saw a man in his late twenties or early thirties, dressed in black with a black cape and walking his even darker dog through the street. I remembered him from about eight years earlier, wearing the same attire, and probably with the same dog. And what occurred to me was that time had stood still for him, he was repeating a repetition compulsion of his own making. He had become a dinosaur in the La Brea pit of Woodstock. After that, I put away forever my visiting Woodstock for the fleeting moment could not be recaptured. I chose to go on and live. Life as rehab, the spell had been broken..

I had experienced a slo-mo epiphany in Woodstock in 1968 and 1969, and a different one now.

Given all this, I can now write about Alice’s Restaurant. Seeing it again on TV, quite by accident, I recalled how it had captured, for all time, at least in my mind, the pace, the slowness, the movement of deeply lived and felt time, the casualness, the sharing and bartering, the exploration of how to be in new relationships that I had experienced in Woodstock. Evolving is a heady experience if you can put off the need to arrive.

Essentially Arlo Guthrie in his first record brilliantly satirized the stupidity and the ridiculousness of authority filled with itself, in this case a police officer in Stockbridge, Mass who cites Arlo and friends with a ticket because they dumped garbage in the town dump. The record takes off from there and satirically goes after the draft system and Whitehall Street where Guthrie as well as myself endured the testing, urine samples, and coughing to check for hernias by demented doctors.

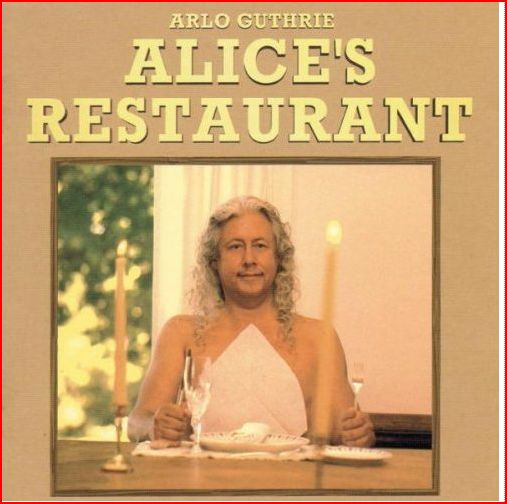

The movie has Guthrie’s music played as rich commentary on some of the scenes which are fictionalized and many which are based on fact. Alice’s Restaurant, if I recall, really was a deconsecrated (mumbo jumbo) church bought by Alice, and thanksgiving dinner was served here as a ritual as a kind. It was a gathering place for all kinds during that time, the young huddled masses of the Sixties. What is very moving is the end when we see Alice standing at the church door and the camera moves away from her ever so slowly past a tree and then another and then it stops so one is left with the passage of time, time stopped, and one is, like I was, haunted by this. It was all over, much like our individual lives when it is time to move on.

The movie has Guthrie’s music played as rich commentary on some of the scenes which are fictionalized and many which are based on fact. Alice’s Restaurant, if I recall, really was a deconsecrated (mumbo jumbo) church bought by Alice, and thanksgiving dinner was served here as a ritual as a kind. It was a gathering place for all kinds during that time, the young huddled masses of the Sixties. What is very moving is the end when we see Alice standing at the church door and the camera moves away from her ever so slowly past a tree and then another and then it stops so one is left with the passage of time, time stopped, and one is, like I was, haunted by this. It was all over, much like our individual lives when it is time to move on.

Leave a Reply